Greetings! The second arc of Orb has begun with a new main character: Orczy the duelist. These are my thoughts on him and the fourth episode as a whole.

Episode 4: The Fact That This World is Far More Beautiful Than Heaven

Episode Rating: 9/10

Orczy and his companion Gras are duelists for hire. Noblemen employ them and send them in their own place to engage in duels with other noblemen. They are basically who you call if you’re rich and don’t want to risk your own hide when challenged to a duel. I have no idea if this was really an occupation in 1400s Europe, but it’s not a huge stretch. We do know about the dueling culture of nobles if nothing else. It make sense that some might hire skilled commoners to fight in their place.

Both Orczy and Gras are interesting characters with good starting concepts. I like them both a lot. Orczy is the more aloof and introverted of the two. He’s also very thoughtful about matters of faith and heaven. His neurotic anxiety and depression about the corruption of the world is almost humorous at certain points, but I understand how he feels. As for Gras, he’s more relaxed, open-minded, and cheerful. The friendship between the two men is strong despite their differences.

Several points stood out to me in Orczy’s rant about heaven. But a large piece is his anxiety about getting accepted into heaven after death. At first, I wandered if Orczy was Calvinist, since he seems to believe in predestination. (Only a few select people will get into heaven, and it’s already been decided who they are.) But this is happening before the Protestant Reformation, so that can’t be right. The Catholic Church would have been in charge of Europe. I’m not sure what they taught back then regarding access to heaven.

The predestination issue shows that the religious lore may not be 100% accurate here. However, the over-arching idea that the world is gross and corrupt is certainly accurate to most branches of Christianity, past and present. That’s what matters most for the character of Orczy. He feels like the world is digusting and his only hope is heaven.

In contrast to Orczy and his outlook, Gras has quite a different perspective. Despite the death of his wife and his subsequent attempted suicide, he now has an optimistic view on life. He’s taken up the study of astronomy as a hobby. It has brought him much joy and existential comfort. The night skies are surely part of the realm of heaven, and even we filthy humans are allowed to gaze at it and study its glory. (That would be Gras’ perspective, not mine.)

For the past two years, Gras has been carefully documenting the path of Mars across the night sky. All indications suggested that it would complete a neat, circular orbit soon. However, when he sees Mars moving backward instead of completing the cycle, Gras begins to despair at life once again. The skies are seemingly not perfect and orderly as he had hoped. Around this time, Gras and Orczy were hired for a special job: to transport a heretic via wagon to his execution site. This night would change their lives.

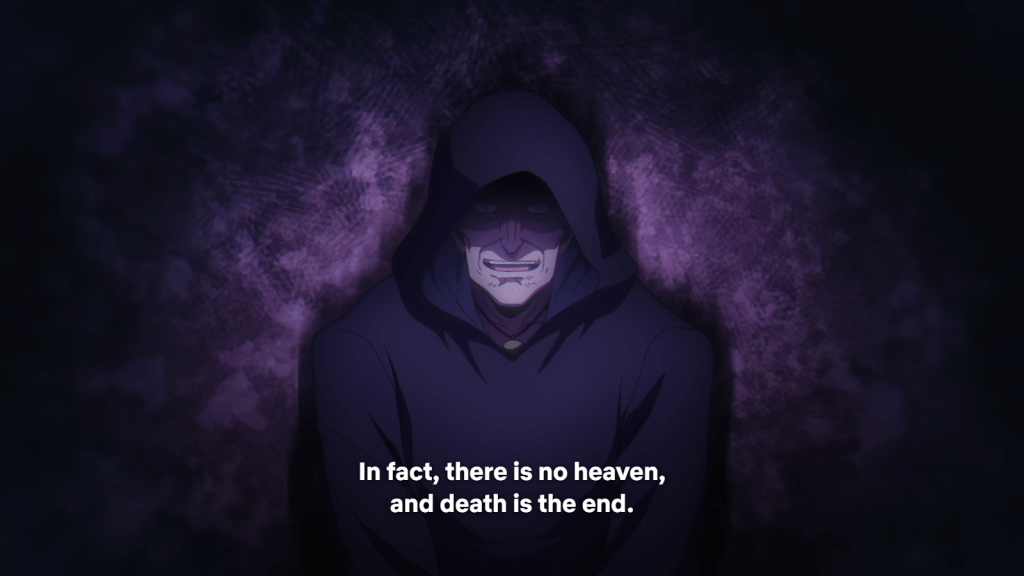

The two armed escorts were not supposed to speak with the heretic, but of course, they did. Orczy said he pitied the old heretic too much to strike him and make him shut up. The discussion with the hooded heretic in the wagon was extremely interesting to me and also well-directed, as we see Orczy and Gras spiraling when faced with ideas that go against Christianity. Orczy desperately tries to deny his doubt, but in the end, Gras gives in. He cuts the heretic’s bonds and agrees to listen to whatever he is trying to pass on.

Specifically, the old man is passing on the location of Rafal’s hidden research materials about heliocentrism. But more broadly, he is arguing for two main points: 1) that there might not be any afterlife, and 2) that reality is more beautiful than the concept of heaven. Both points serve to direct one to appreciate one’s own mortal life – the only life any of us are sure that we have. This is definitely against the core of Christian doctrine, which compares our current world to “dirty rags” to wipe our feet on as we cross into the (unproven) afterlife.

(Side Note: In case anyone was tempted to point it out, I am aware that not every modern Christian discounts the value of our reality. Many individuals have embraced more secular ideas like appreciation for the current world. But it should be acknowledged that, while I’m happy to see modern Christians adapting, there isn’t actually room for that in the traditional doctrine. It’s a fascinating topic worth looking into if you like learning about theology.)

The talk with the heretic was truly a fascinating scene. I could comment on several more points, like what he meant with the comment about an Athenian two thousand years ago. Look that up yourself if you want. The last point I’ll address is what the heretic said about why faithful people are afraid of him. It’s not because they see him as an alien existence, an outsider. Rather, it’s because they see themselves in him and are terrified to admit their doubts.

“This man lost his faith. That could happen to me, too.” That’s a scary thought when your community and your understanding of the world are all caught up in religious faith.

As scary as it is, though, I recommend everyone embrace their religious doubts and conduct research to acquire more information. Some people do that and land in a place of agnosticism or atheism (like myself). Others maintain their supernatural hopes and beliefs, but become better people with more humanistic ideas. Being an atheist isn’t really important compared to treating others well and appreciating our reality. We have nothing to fear from the truth, so always investigate.

~Thanks for reading~